Flash! A New Report from 1970!

We are pleased to present some newly written track history courtesy of Don Winchester. Here is the first installment of Don's work, which describes in rich detail his first-hand view of competiting at the track, while also filling us in about that time and that place when the speedway was newly reborn. And he includes lots of details too: things that many of us never saw from our seat in the grandstands, or that may have turned a fuzzy as the years have passed.

If you are not familiar with Don, he competed in modified mini stocks, and spent several years as the track photographer. Although he has contributed hundreds of pictures to this site, I don't have a single one of Don to show you!

Florida City Speedway, 1970 – Opening Night With Don Winchester

Part 1; The Track

Leaning over the little engine tucked under the back deck of my Renault R-8, I checked the dip stick one more time before the start of the night’s climatic event – the Modified Mini Stock feature – of the grand re-opening of Florida City Speedway in 1970. As the little 1/5th mile began operation under Southern Mini Stock Racing Association (SMSRA) control, the infamous Everglades heat and humidity definitely weren’t the only things hanging in the air. Anxiety was a huge ingredient, as well.

Yeah, on that hot, August Saturday night, there was plenty of anxiety. The SMSRA was anxious for the event to go off well and find a permanent racing home track. The Florida City citizens were anxious for the return of some wholesome, exciting, inexpensive Saturday night entertainment. And I, like everybody else shoving a car through the pit gate, was anxious that my self-built little green and black hot-rod would simply be competitive.

And competitive was what this place was all about. The tiny, well-banked bullring always brought action to the fans and often frustration to the drivers as well. With little room to race and less room to pass, tin-bending action was guaranteed. If things went well, the pass was made. If things didn’t… well, it was wood chips in the radiator and more big wrinkles in the bodywork.

The acrid but familiar odors of overheated engine oil and overworked tire rubber added to the heavy atmosphere, too, as the Stock class cars finished their main just a few feet away from me. The sounds of competition were loud enough – parked as I was against the backside of the fourth turn banking – but they were amplified even more by the tall, naked brick walls enclosing the entire facility and topped by barbed wire – just in case the loonies inside should try to escape. Ear plugs might have helped but nobody even considered using such a prissy item back in those days. Every now and then, you’d see somebody who’d ripped the filters off a couple of his Viceroys and stuffed them into his ears if his headache was bad enough.

As I checked the plug wire connections, sweat soaked my brown hair from humidity that would choke an alligator. It ran down my forehead and fell onto the lenses of the black plastic, horn-rimmed glasses I hated, not because they were horn-rimmed, a fashionable feature of the day, but because they were always in the way, filling up with sweat. The sweat clouding the lenses always added an extra dimension to the problem of seeing anything smaller than a full-size race car in the rather dimly lit pit area. Generators and utility lights to illuminate your own temporary piece of Florida City real estate were items that would only make their way into the lives of Weekend Warrior racers in the far, distant future. Heck, we were lucky if we had a trailer!

The grass that carpeted the pit area stained the knees of my jeans as I pressed my pencil gauge onto the tire valve of the widened, welded steel wheels that stuck well outside of the cut out fenders on every corner of my low machine. The darkness complicated the Braille-like search through the individual grass blades for the plastic stem valve cap that invariably fell from my callused fingers. You couldn’t use tubes in the flimsy racing tires because they were too hard to find in that combination of 10-inch width and low profile 13-inch racing tire and you would rip the stems off anyway so the tires always leaked air. Sometimes they would lose five psi in the course of a feature! If the tires were holding air within a pound or two of their original setting, I knew I could make it through the feature and that was good enough. Otherwise, it meant another can of tire sealant.

My spot in the pits was determined by my arrival and sign-in at the pit gate. That was usually relatively late since I would leave my job as a line mechanic at noon, go hitch up and load up, then drive all the way from Ft. Lauderdale – a real long ride in the days before turnpike extensions. I had to creep and bump down the very rural Krome Avenue from the Tamiami Trail dodging tractors, fruit-bearing semi trucks and really big, mis-aimed sprinklers. Pit space was very limited at the little track with cars crammed door handle to door handle within the three cinder block perimeter walls, the banking and the grandstands so everybody had to unload their stuff and park their trailer (if they had one) outside the pit entrance, on the street. But once you got into the track, it really was a pretty clean, well-engineered little place to race, for the period.

The entrance onto the racing surface from the pits was off the outside of Turn Four, onto the front straight. You exited the track by driving straight up the banking and over the edge of the 3rd turn. There were incidents when the exit from the racing surface into the pits was definitely not intentional.

The track was well banked but narrow and tight. You could get four cars abreast from the infield grass across the asphalt to the low, 2x12 wood plank retaining fence that encircled the track. However, getting just two abreast during a race was not for those with any timidity, whatsoever. Unless you were lapping somebody who wouldn’t move over, you would only get out there by error or some ‘friendly’ assistance from behind. But once in that unenviable position, you had to learn to trust that the other guy was gonna to keep his four wheels going where you expected or it was more wood chips and a ruined night.

The boards of the retaining fence overlapped the next board at each wooden support post toward the direction of travel. Like a ratchet. You could rub it going the right way and not catch much wood – just the last few feet of each protruding board. But if you hit it hard they would give way until you got to the deeply embedded vertical post for the sudden, final, suspension-shearing stop.

With the straights banked nearly as much as the turns, the grandstands were elevated about six feet up to track level along the front straight and there was a 4-foot, chain-link debris fence around the outside of the retaining fence. In hindsight, I don’t think it stopped much debris, I guess it’s main purpose was keeping the fans away from the track surface when they didn’t agree with what may have transpired out there. A pass-through existed at the start line from the board walk at the bottom of the grandstands to the track surface, which also served as the flagman’s station. The grandstands were about 10 or 12 rows high, the top row visible over the block wall that separated the track from the road with the neighboring houses directly across the street.

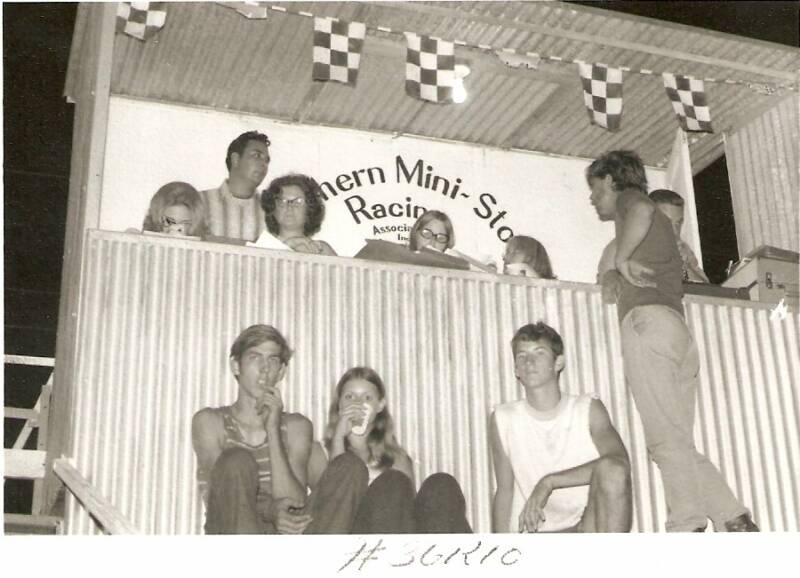

A small, somewhat ramshackle (but freshly painted) open-front, covered booth stuck together with old pieces of thin plywood, commanded the middle of the top row directly above the finish line and served as scoring tower for Rob Bean’s girlfriend, Sandy, Ritchie Vonderheide’s announcing booth and general official nerve center for each evening’s activities.

Despite the banking, because of the tight turns and short straights, it really was one groove. If you could bide your time behind somebody, mistakes were easy to make so when somebody in front of you made one, you could slip under his sliding racer as he pedaled to keep it off the 2x12s and get the inside line into the next corner.

Unfortunately, rooting and gouging were the predominant way to advance. You had to be a fair bit faster than the competitor you were challenging to succeed in a clean, outside pass but it could be done with great patience and no errors. And while you were patiently hanging out there working your way forward, inch by inch, lap after lap, the guy you were chasing – who had twice as much racing line to work with – was moving farther and farther out of reach. And of course, the guy chasing you was turning the bumper of the guy inside of you into a piece of scrap. I don’t need to tell you that riding outside of a guy who was struggling BEFORE he got hit was not THE place to be.

And did I say the track was small? At around 11 seconds a lap, you didn’t have much time to do much of anything other than keep the car under you. The starting order was usually inverted according to your points earned in the last four weeks of racing so patience wasn’t a commodity in great evidence. There was little time to move through a 15- or 20-car field – a 30-lap feature could be over in a bare flash of time – so you had better be ready to drive… or be driven over.

Some of this I already knew and there was a lot more I was going to learn… stuff I didn’t even know I didn’t know. I had managed to retain my pole starting position by winning my heat race. But as I closed the deck lid on the Renault before that first feature at this new track, my head was full of anticipation and anxious for the experience to begin. And it would be quite an experience.

Next Installment; The Cars